Ptah: The Divine Creator and Master Craftsman of Ancient Egypt

From the earliest dynasties through the late periods of Egyptian civilization, Ptah maintained a central position in Egyptian religious thought, embodying the power of creation through thought and speech.

Introduction

Ptah stands as one of ancient Egypt's most profound and enduring deities, revered as both creator god and patron of craftsmen. From the earliest dynasties through the late periods of Egyptian civilization, Ptah maintained a central position in Egyptian religious thought, embodying the power of creation through thought and speech. His worship, centered in Memphis—Egypt's ancient capital—spread throughout the land and beyond, influencing religious practices for over three millennia.

Origins and Early Worship

Ptah was worshipped in Memphis from late prehistory, with evidence of his cult dating back to approximately 3100 BCE. Initially serving as the local protective deity of Memphis, his importance grew exponentially when Memphis became the capital of unified Egypt around 3000 BCE. The political significance of Memphis as the administrative center of Egypt directly contributed to Ptah's rise to national prominence.

The name "Ptah" (ancient Egyptian: ptḥ, reconstructed as *piˈtaħ*) most likely derives from root words meaning "to sculpture," "to fashion," or "to engrave," reflecting his fundamental association with craftsmanship and creation. Unlike many Egyptian deities whose iconography evolved over time, Ptah's visual representation remained remarkably consistent throughout Egyptian history—a testament to his role as a symbol of stability and continuity.

Iconography and Symbolism

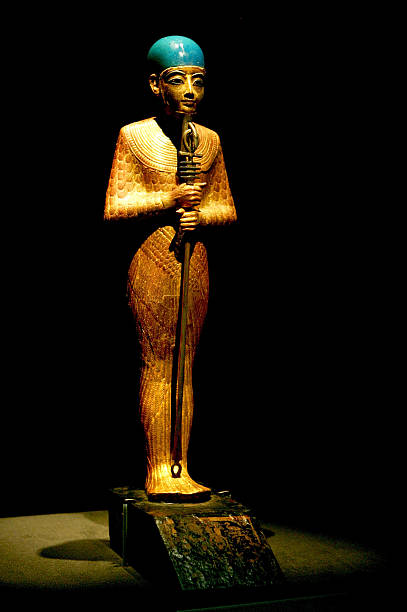

A traditional representation of Ptah showing his distinctive mummiform appearance and divine attributes.

Ptah is depicted with distinctive and unmistakable features. He appears as a mummified human figure with green skin (symbolizing rebirth and fertility), enveloped in a tight-fitting shroud that leaves only his face, ears, and hands visible. His head is covered by a close-fitting skullcap, and he wears a short, straight false beard typical of divine figures. In his hands, he holds a composite scepter combining three powerful symbols: the was (power), the ankh (life), and the djed (stability)—representing the three creative powers of the god.

Ptah typically stands or sits on a pedestal representing Maat, the goddess of truth, justice, and cosmic order. Behind his neck hangs the menat necklace, symbolizing divine protection. This austere, unchanging appearance serves as a metaphor for stability, continuity, fertility, and authoritative command—the main features of Egyptian kingship and cosmic order.

The Memphite Theology: Creation Through Thought and Speech

The theological conception of Ptah as supreme creator is most fully articulated in the text known as the Memphite Theology, preserved on the Shabaka Stone. This basalt stela, dating to the reign of Pharaoh Shabaka (approximately 712-698 BCE) of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, claims to be a copy of a much older worm-eaten document that the king ordered preserved for posterity.

The Shabaka Stone presents a sophisticated creation account that distinguishes Ptah's method from other Egyptian cosmogonies. While the better-known Heliopolitan creation myth describes Atum creating through physical generation (taking his seed in hand and mouth), the Memphite Theology presents Ptah as creating through intellectual and verbal power:

"There comes into being in the heart. There comes into being by the tongue. It is as the image of Atum. Ptah is the very great, who gives life to all the gods and their kas. It all in this heart and by this tongue."

In this theological framework, Ptah's heart (representing mind and thought) conceives creation, and his tongue (representing speech and command) brings it into existence. This process emphasizes the simultaneity of thought and materialization—what is conceived in Ptah's heart is instantly spoken into being by his tongue. The text describes how Horus came into being in Ptah as mind, and Thoth came into being in Ptah as tongue, positioning these major deities as manifestations or functions of Ptah's creative power.

This creation theology represents a remarkable intellectual achievement in ancient religious thought. Rather than relying on mythical physical generation, it presents creation as resulting from divine intellect and command—a concept that would resonate through later religious traditions. The Memphite priests emphasized that Ptah created "in the form of Atum," encompassing and superseding the Heliopolitan system while acknowledging its traditional importance.

Ptah's Cosmic Roles and Manifestations

The Memphite Theology presents Ptah as all-encompassing, manifesting in multiple forms that span the entire cosmic order:

Ptah-Nun

"The father who made Atum"—connecting Ptah to the primordial waters of chaos from which creation emerged

Ptah-Naunet

"The mother who bore Atum"—emphasizing Ptah as both father and mother of creation

Ptah-Tatenen

Associating Ptah with Ta-tenen, "the risen land," the primordial mound that emerged from chaos

Ptah-the-Great

"Heart and tongue of the Ennead"—the cosmic intelligence behind the pantheon

This theological framework presents a form of pan-en-theism, where all deities exist "in" Ptah as manifestations of his singular creative power. Every god and goddess represents a divine word thought in Ptah's mind and spoken by his tongue. The text proclaims: "Thus Ptah was satisfied after he had made all things and all divine words."

Patron of Craftsmen and Architects

Beyond his cosmic role as creator, Ptah maintained strong associations with earthly craftsmanship. He was the patron deity of craftsmen, sculptors, architects, metalworkers, and artisans of all kinds. His high priest bore the title "chief controller of craftsmen" (wer kherep hemut), emphasizing this connection.

The legendary architect Imhotep, designer of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara and later deified, was considered the son of Ptah. This association linked Ptah directly to Egypt's most impressive architectural achievements, including the pyramids of the Giza Plateau. The god represented not just the abstract principle of creation but the practical skill, design, and execution required to transform ideas into physical reality.

Ptah embodied the transformation of concept into object—the entire creative process from initial thought through planning to final material form. In Egyptian understanding, he created both objects and their hieroglyphic representations simultaneously, linking written language with physical reality and emphasizing the power of words to shape the world.

The Memphite Triad

Ptah belonged to the Memphite Triad, a family grouping that included:

Ptah

The creator god and divine father

Sekhmet

His consort, the powerful lion-headed goddess associated with both destruction and healing

Nefertem

Their son, the god of perfumes and the blue lotus, representing "He Who is Beautiful" and the first light of creation

This triad was particularly prominent from the Late Period onward and played a central role in Memphis's religious life. The combination of creative power (Ptah), protective fierceness (Sekhmet), and youthful renewal (Nefertem) represented a complete theological system encompassing creation, preservation, and regeneration.

Syncretism and Composite Deities

Throughout Egyptian history, Ptah was frequently combined with other deities, reflecting both his importance and the Egyptian tendency toward religious syncretism:

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris

A composite deity combining Memphis's creator god with Sokar (the falcon-headed god of the Memphite necropolis) and Osiris (ruler of the underworld). This form became particularly important in funerary contexts.

Ptah-Tatenen

Merging Ptah with Tatenen, the primordial earth deity, emphasizing his role in bringing forth the land from chaos.

Ptah and Atum-Re

In New Kingdom theology, particularly during the Amarna period, Ptah was sometimes identified with aspects of the sun gods Re and Aten, with Ptah providing the divine essence that fed the sun god's existence.

The Leiden Hymns from the reign of Ramesses II present an especially sophisticated syncretism, treating Amun, Re, and Ptah as essentially three aspects of one divine entity: Amun as the hidden name, Re as the face, and Ptah as the body.

The Sacred Apis Bull

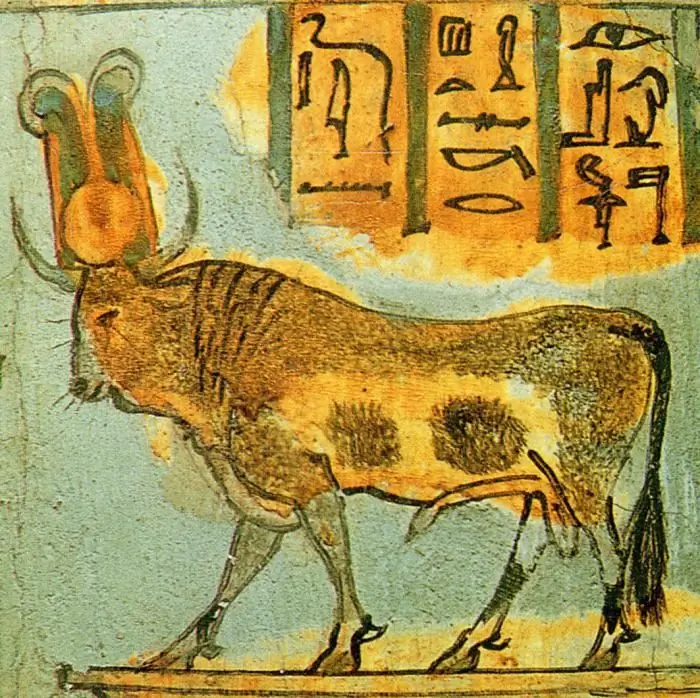

In Memphis, Ptah's temple housed the sacred Apis bull, considered a living incarnation or manifestation of the god. The bull served as Ptah's oracle, allowing the god to communicate with worshippers and give divine guidance. When an Apis bull died, it was buried with full honors befitting a deity and was believed to merge with Osiris, becoming Osiris-Apis (later Serapis in the Greco-Roman period).

The Apis bull cult represented one of the most important animal cults in ancient Egypt, drawing pilgrims from across the land. The careful selection, maintenance, and eventual burial of these sacred animals demonstrated the intimate connection Egyptians perceived between the divine and natural worlds.

The Great Temple of Memphis

The temple of Ptah in Memphis, known as Hut-ka-Ptah ("Enclosure of the ka of Ptah"), ranked among the three largest and best-endowed temples in ancient Egypt. Though little remains of this magnificent structure today, ancient sources describe it as one of the most prominent religious centers in the ancient world.

The temple's Egyptian name, Hut-ka-Ptah, entered Greek as Aiguptos, passed into Latin as Aegyptus, developed into Middle French as Egypte, and was finally borrowed into English as "Egypt." Thus, the very name of the nation derives from Ptah's temple, demonstrating the god's central importance to Egyptian identity.

The temple complex served multiple functions: as a site for worship and festivals, a center for priestly training and theological study, housing for the sacred Apis bull, and a workshop for craftsmen under Ptah's patronage. The high priest of Ptah wielded considerable political and religious authority, often serving as an advisor to the pharaoh.

Ptah in Egyptian Ritual and Magic

Ptah played a crucial role in the "Opening of the Mouth" ceremony, an essential funerary ritual that restored the senses and faculties of the deceased (and animated cult statues). His presence in this rite emphasized his power to grant life and enable communication between the worlds of the living and dead.

The Egyptian concept of heka (magic) was intimately connected with the power of words and names. Ptah's creation through speech aligned with the broader Egyptian understanding that properly spoken words possessed inherent power to shape reality. This belief permeated Egyptian magical practices, religious ceremonies, and even governmental administration, where royal decrees were understood as performative utterances that created the reality they described.

Historical Development and Dating Controversies

The dating of the Memphite Theology has been subject to scholarly debate. While the extant text on the Shabaka Stone dates to approximately 700 BCE, its content likely draws on much older traditions. Early scholars, including James Henry Breasted, dated the original text to the Old Kingdom (First to Fifth Dynasty, approximately 2686-2345 BCE). However, more recent philological analysis, particularly the work of Friedrich Junge (1973), has demonstrated that the language and grammar of the text point to a New Kingdom origin, probably from the Ramesside period (Nineteenth or Twentieth Dynasty, approximately 1292-1075 BCE).

The text itself claims to be a copy of an ancient worm-eaten document discovered by Shabaka, suggesting a tradition of preserving and updating important religious texts. This narrative fits the political context of Shabaka's reign: as a Kushite (Nubian) pharaoh establishing control over a reunited Egypt after the Third Intermediate Period, he needed to legitimize his rule by connecting it to ancient Egyptian traditions. The "rescue" of this important Memphite text served his political purposes while preserving genuine theological traditions.

Spread of Worship and Cultural Influence

While Memphis remained the primary center of Ptah's worship, his cult spread throughout Egypt and beyond. Smaller temples dedicated to Ptah existed at many sites, including Karnak, Gerf Hussein, and various other locations. His association with craftsmanship made him popular wherever skilled artisans worked.

The Phoenicians played a significant role in spreading Ptah's worship beyond Egypt's borders. Archaeological evidence, including statues and votive figures, demonstrates Ptah's veneration in Carthage and other Phoenician colonies across the Mediterranean. This international spread reflects both the far-reaching influence of Egyptian religion and the universal appeal of a deity associated with skilled craftsmanship.

The Greeks identified Ptah with Hephaestus, their divine blacksmith and craftsman, while the Romans in turn equated Hephaestus with Vulcan. This cross-cultural identification demonstrates how Ptah's essential characteristics—as divine craftsman and maker—translated across different religious systems.

Theological Significance

The Memphite Theology represents a sophisticated development in ancient religious thought, moving beyond purely mythical or physical explanations of creation toward a more abstract, intellectual understanding. By presenting creation as resulting from divine thought and speech rather than physical generation, it anticipates theological concepts that would later appear in other traditions.

The text's emphasis on the simultaneity of thought and materialization, the creative power of divine speech, and the all-encompassing nature of the creator deity represent remarkably advanced theological concepts. The Memphite system attempted to harmonize different creation traditions by positioning Ptah as the ultimate source from which all other creator gods (including Atum-Re) emerged.

This theology also addressed fundamental questions about the relationship between mind and matter, thought and reality, unity and multiplicity. By making Ptah both transcendent (existing before creation as Ptah-Nun) and immanent (manifesting in all created things), it developed a form of pan-en-theism that would influence later mystical traditions.

Legacy and Continued Influence

Ptah's worship continued throughout Egyptian history into the Greco-Roman period, demonstrating remarkable staying power across millennia of cultural change. His association with skilled craftsmanship, his role as creator deity, and his connection to Egypt's capital city ensured his continued relevance through changing dynasties and religious reforms.

The concept of creation through divine speech found in the Memphite Theology resonates with creation accounts in other traditions, particularly the emphasis on the creative power of divine word or logos. This parallel has attracted considerable scholarly attention and debate about possible influences or independent development of similar theological concepts.

Today, Ptah remains one of the best-known Egyptian deities, recognized for his distinctive mummiform appearance and his profound role in Egyptian religious thought. The Shabaka Stone, housed in the British Museum, continues to be studied as one of the most important documents in the history of Egyptian theology and philosophy.

Conclusion

Ptah embodies the Egyptian understanding of creation as both cosmic event and ongoing process, divine conception and material manifestation, eternal principle and temporal craft. As the god who "gave birth to the gods" and "made all things," he represents the fundamental creative principle underlying reality itself. His unchanging iconography across centuries of Egyptian history symbolizes the permanence and stability that Egyptians sought in their cosmic and social order.

From the grand temple complexes of Memphis to the humble workshops of craftsmen, from the highest theological speculations to the practical work of daily life, Ptah's influence permeated Egyptian civilization. His theology of creation through thought and speech represents one of ancient Egypt's most sophisticated intellectual achievements, positioning him not merely as one deity among many, but as the very source and sustainer of all existence—the beautiful face of divine creativity manifesting throughout the cosmos.

References

Encyclopedia and Overview Sources:

- Britannica Editors. "Ptah: Creator God, Memphis, Patron." Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Britannica Kids Editors. "Ptah." Britannica Kids.

- "Ptah." Encyclopedia.com - Myths and Legends of the World.

Primary Source Texts:

- "The Shabaka Stone (Memphite Theology)." Attalus.org. Full translation.

- British Museum. "Shabaka Stone" (Object EA498). Collection page and transcript.

- British Museum. "Shabaka Stone Transcript: Hieroglyphs Unlocking Ancient Egypt." PDF.

- Breasted, James H. "The Memphite Theology" (translation and commentary).

Academic and Scholarly Sources:

- Bodine, J.J. "The Shabaka Stone: An Introduction" (2009). Studia Antiqua.

- Lesko, Leonard H. Translation reference. Omnika.org.

- Van den Dungen, Wim. "The Shabaka Stone: Ancient Egypt - Memphite Theology." Sofiatopia/Maat. Comprehensive overview and analysis.

Museum Collections:

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Ptah" (search results showing statues and cult images).

Secondary Sources and Modern Interpretations:

- "Ptah." Wikipedia.

- "Ptah, Maker of Things." Tales from the Two Lands (January 28, 2022).

- "God Ptah: The Artisan God of Ancient Egypt." EgyptaTours (February 4, 2024).

- Henke, Adrian. "9 Surprising Facts about the Egyptian God Ptah." TheCollector (October 3, 2020).

- "Ptah: The Local God of Memphis Who Eventually Became the Creator." Timeless Myths (March 8, 2024).

- "Ptah: Egyptian God of Crafts and Creation." History Cooperative (March 17, 2025).

Educational Resources:

- Study.com. "Ptah: Symbols, Temples & Role in Egypt" (lesson overview).

Note on Additional Scholarship:

For peer-reviewed academic research, readers should consult JSTOR, Project MUSE, or Google Scholar using search terms such as "Ptah," "Memphite Theology," "Shabaka Stone," "Ptah Memphis," and authors including Leonard H. Lesko, J.J. Janssen, Jan Assmann, Erik Hornung, Henri Frankfort, and Friedrich Junge.